December 2023

For both your AAT Level 3 and Level 4 studies, you will be required to calculate depreciation. Karen Groves explains how to do it.

Depreciation is the reduction in value of an asset mainly due to wear and tear, and obsolescence, for example, caused by changes in technology.

If you purchased a new car today it would not be worth the same as what you paid for it in a year’s time – the drop in value is called depreciation.

The non-current asset will be shown at cost on the Statement of Financial Position, together with accumulated depreciation and the carrying amount for your Level 3 studies. At Level 4 the carrying amount only is shown with the depreciation calculations shown in the notes to the financial statements. The accumulated depreciation represents the total amount of depreciation charged to date. The carrying amount represents what the asset is worth now (cost minus accumulated depreciation).

Depreciation is an estimate, and it is very unlikely an asset would be sold for the same amount as the carrying amount.

How do we calculate depreciation?

Before calculating depreciation, we need to establish if there is a residual value. The residual value is the amount that the business expects the asset to be sold for at the end of its useful economic life; however, this isn’t assessed in every question. The useful economic life can be in years or in activity output.

There are three methods of calculating depreciation as follows, with the most suitable method being chosen by management:

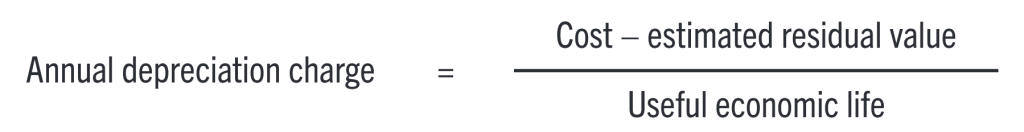

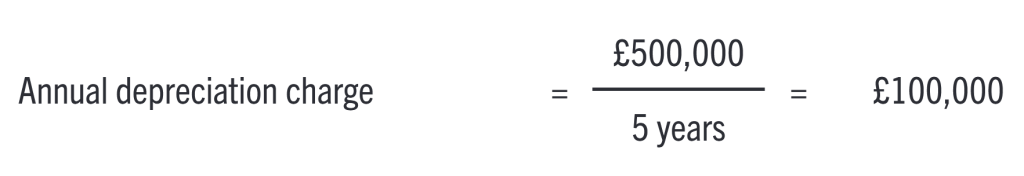

Straight Line

This method assumes that the asset will have the same amount of depreciation charged each year, so a consistent amount charged over the asset’s useful economic life.

Example:

Or:

Cost – estimated residual value x percentage given = annual depreciation charge.

If a business purchased an asset with a cost of £500,000 and an expected useful economic life of five years, we would calculate the depreciation as follows:

Reducing Balance (also called Diminishing Balance)

This method assumes a higher amount of depreciation to be charged in the early years, which reduces over time. The method uses the carrying amount of the asset to base the depreciation calculation on rather than the cost.

Example:

Annual depreciation charge = Carrying amount x %

If a business purchased an asset with a cost of £200,000 and depreciates this at 15% per annum using the reducing balance basis, we would calculate the depreciation as follows in the first year:

Annual depreciation charge = £200,000 x 15% = £30,000

For the second year the calculation would be:

Annual depreciation charge = £200,000 – £30,000 x 15% = £25,500

As you can see, the depreciation amount reduces every year.

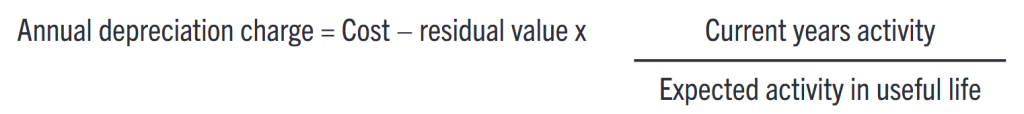

Units of Production

This method is based on usage of the asset, so more activity equals a higher depreciation charge, lower activity equals a lower depreciation charge.

Example:

If a business purchased machinery with a cost of £120,000 and an expected useful economic life of 60,000 machine hours, we would calculate the depreciation as follows, if the year one machine hours used were 12,000

A further example of an asset that this method would be suitable for could include a photocopier, which has an average life of a set number of photocopies.

Questions

- If a business purchased an asset with a cost of £700,000 and an expected useful economic life of five years, what would be the annual depreciation charge?

- If a business purchased an asset with a cost of £400,000, estimated residual value of £50,000 and an expected useful economic life of four years, what would be the annual depreciation charge?

- If a business purchased plant and machinery with a cost of £880,000 and an expected useful economic life of 200,000 machine hours, what would be the annual depreciation charge if the year one machine hours used were 10,000?

Answers

- Karen Groves is an AAT tutor and AAT Faculty Director at e-Careers